Mare Orientale, "the Eastern Sea" is on the far left or Western Limb of the Moon as seen from Earth after a Full Moon. To see why the Eastern Sea is viewed on the West take this opportunity to view the full-sized version of the image greatly reduced above. What you will see a world class, "amateur" but truly state-of-the-art video still mosaic of a late crescent Moon assembled by the guys Charles Wood calls "the Minsk miracle boys" in Belarus. They post their astounding work at Astrominsk.

When we move in on as much as this template will allow, on the actual size of the late Crescent Moon as seen in the Mosaic from Minsk, the flat Thumbnail Moon seen with a naked eye from Earth is now rich with detail, like pond water under a microscope. The foreshortened view around the curve of the lunar globe reveals fine structure. On the right in the frame above is Rima Sirsalis for example, bisecting the 32 kilometer-wide crater De Vico A. Distances are greater along our line of sight as our eye approaches the limb where the spectacular Mare Orientale basin straddles the borderline between the Moon's Near and Far sides, with much of its detail inside the libration zone. It is seen in profile as the Moon turns its head and back again, wobbling through the Near Side's tidal lock with Earth.

Ahead of the Moon in it's orbital path. If you left Earth orbit headed out toward the Moon like Apollo, on a "free-return trajectory," after 100 hours or so your initial velocity will have steadily slowed to a relative crawl by the time you approached the highest point of your ballistic path. If you timed the whole thing correctly this high point would correspond with a point somewhere ahead of the Moon in its orbit. As you wait for the Moon's gravity to increase your speed for a slingshot around its Far Side you would find yourself looking down at the Moon's "leading" Western Hemisphere. The cannon shot seen just below the Moon's equator is Mare Orientale, dividing the mostly basalt-filled lowland basins of the Near Side with the highland craters of the Far Side. Our target of interest is at the center of the circular smudge on the southwestern mountainous rings surrounding Orientale's central basin [Virtual Moon Atlas v.4].

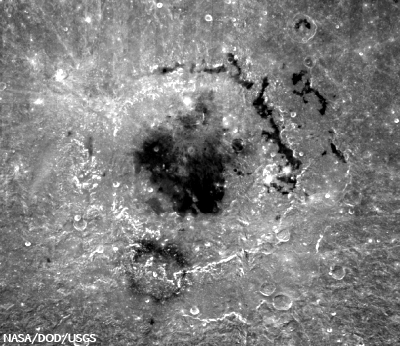

More than forty years ago Lunar Orbiter IV captured the image above of the same Western Hemisphere, close to the time of a Full Moon down on Earth. Although our smudgy target is still awaiting sunrise, the long shadows of early dawn sketch out the rings and rooks surrounding the central basin with rich relief. The degree of the Moon's wobble brings the central basin and the rings and often the flooded lakes of the east side of the impact into view from Earth. Though broadly hinted to patient observers over centuries, the full extent of the basin's detail was not really known until photographs like this one became available. Unlike the more familiar Near Side seas, Orientale still has it's surrounding concentric mountainous ring structure still highly intact, hinting that the "impact forming event" that created it was either unusually energetic or more recent [IV-187-M USGS].

Efforts to map the widely varying elevations on the Moon reached a plateau with Clementine (1994), until the recent, far more dense dataset gathered using laser altimetry by Japan's Kaguya (which is only now being released) and the LOLA package on-board the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter sent by the United States became more available. Comparing apples with apples, the images above and below represent the same area on the Moon and the best improvements on the Clementine dataset available through the web-based Map-A-Planet service by the U.S. Geological Service. Above we can see what could not be easily understood using photography alone. Orientale's mountainous rings and rooks are largely intact but the basin's impact zone straddles more than just the Near and Far side longitudinally. It also lies along a distinct and global change in elevation, steadily moving toward the west and the rim of the massive South Pole Aitken Basin hundreds of kilometers outside our view on the left.

And in the second Map-A-Planet image our "smudge" on the southwestern side of mountain rings surrounding Orientale has become visible again. It appears to be mostly invisible to laser light at this scale (the map above and the color topography further up are each 900 km high and 1300 km from east to west). It is superficial, representing a change in optical reflectivity, maybe the remains of a plume, an eruption from it's center dusting the surface or changing its composition. This image come from the second improved version of a global albedo map produced using Clementine data collected in 1994. And we can see what appears to be a round feature, a crater near the center of the "smoke ring." For scale the basin at the center of Orientale is about 300 kilometers across. The smudgy smoke ring is 143 kilometers in diameter and the structure at it's center seems to be between 6.5 and 14 kilometers across.

More than forty years ago Lunar Orbiter IV captured the image above of the same Western Hemisphere, close to the time of a Full Moon down on Earth. Although our smudgy target is still awaiting sunrise, the long shadows of early dawn sketch out the rings and rooks surrounding the central basin with rich relief. The degree of the Moon's wobble brings the central basin and the rings and often the flooded lakes of the east side of the impact into view from Earth. Though broadly hinted to patient observers over centuries, the full extent of the basin's detail was not really known until photographs like this one became available. Unlike the more familiar Near Side seas, Orientale still has it's surrounding concentric mountainous ring structure still highly intact, hinting that the "impact forming event" that created it was either unusually energetic or more recent [IV-187-M USGS].

Efforts to map the widely varying elevations on the Moon reached a plateau with Clementine (1994), until the recent, far more dense dataset gathered using laser altimetry by Japan's Kaguya (which is only now being released) and the LOLA package on-board the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter sent by the United States became more available. Comparing apples with apples, the images above and below represent the same area on the Moon and the best improvements on the Clementine dataset available through the web-based Map-A-Planet service by the U.S. Geological Service. Above we can see what could not be easily understood using photography alone. Orientale's mountainous rings and rooks are largely intact but the basin's impact zone straddles more than just the Near and Far side longitudinally. It also lies along a distinct and global change in elevation, steadily moving toward the west and the rim of the massive South Pole Aitken Basin hundreds of kilometers outside our view on the left.

And in the second Map-A-Planet image our "smudge" on the southwestern side of mountain rings surrounding Orientale has become visible again. It appears to be mostly invisible to laser light at this scale (the map above and the color topography further up are each 900 km high and 1300 km from east to west). It is superficial, representing a change in optical reflectivity, maybe the remains of a plume, an eruption from it's center dusting the surface or changing its composition. This image come from the second improved version of a global albedo map produced using Clementine data collected in 1994. And we can see what appears to be a round feature, a crater near the center of the "smoke ring." For scale the basin at the center of Orientale is about 300 kilometers across. The smudgy smoke ring is 143 kilometers in diameter and the structure at it's center seems to be between 6.5 and 14 kilometers across.

A much closer look at the Clementine albedo map shows why it was less than clear what the diameter of the smoke ring's central feature might be. As late as the Apollo Era there was an serious debate over the origin of the Moon's intense cratering. Many clung to the idea that most of these had to be volcanic in origin. While the impact theory ultimately won the day that did not mean there were not volcanic vents on the Moon's surface. This one was described as "a kiss on Mare Orientale" in a census of these pyroclastic features in recent years. Traced out on the map are the respective lengths of two stereo photographs made of the area using the narrow angle camera (NAC) on-board the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO). The ovals designate the approximate location of LRO at the time each image was taken. The Moon revolves slowly under LRO's orbit, but it does revolve, eventually bringing the whole of the Moon's surface under the vehicle's survey. NAC Image M102795327 was taken during orbit 321 and M102802486 during orbit 322.

Flying northward from the south, Japan's lunar orbiter Kaguya took a fantastic High Definition Television sequence covering the length of the entire Orientale region. Passing to the port side of the orbit is our "Kiss." According to those who actually orbited the Moon, the Kaguya HDTV stills and sequences were very much as they remembered the appearance of the surface to have been looking out of the Apollo windows. Judging by the shadows this sequence from 2008 appears to have been taken under a full sun. The northern arc of the relatively dark, more "optically mature" smoke ring surrounding the oblong vent can would be visible to the naked eye at this distance [JAXA/NHK/SELENE].

Around the same time as the regional HDTV sequence or the Orientale Basin was taken, Kaguya took some equally fantastic looks downward along its orbit and gathered the Terrain Camera image of our "Kiss" vent. The image was taken as a comparison with images of the same feature using the orbiter's Multi-Band Imager. Here we see the surface albedo in a glory unsurpassed until barely a year later.

But this is the detail we are looking for, and it's easy to see why some have argued that the level of detail being downloaded from the LRO as we move into 2010 has made it difficult to understand without the kind context. very humbly presented here. Three images further up and you can see the length of the original image (LRO NAC M102802486 R), and one image further up allows the rubble along the rim of the pyroclastic "kiss" to be seen.

Above you can see that rubble at centimeter scales. The image is 800 lines of 52224 lines in height and 400 lines of 5064 samples across. The only better way to examine such detail is directly, sampling the rich database being tested for release next March and long before the first half of the LRO survey is complete.

Another better method of course would be to take a hike on the rim of the Kiss. Had someone been in the middle of that hike, stumbling over the boulders above, LRO would have easily caught their progress, along with each dusty foot print.

LRO is a necessary precursor mission before "extended human activity" on the Moon can begin, for the first time. As the dataset grows the results themselves show us why.

Above you can see that rubble at centimeter scales. The image is 800 lines of 52224 lines in height and 400 lines of 5064 samples across. The only better way to examine such detail is directly, sampling the rich database being tested for release next March and long before the first half of the LRO survey is complete.

Another better method of course would be to take a hike on the rim of the Kiss. Had someone been in the middle of that hike, stumbling over the boulders above, LRO would have easily caught their progress, along with each dusty foot print.

LRO is a necessary precursor mission before "extended human activity" on the Moon can begin, for the first time. As the dataset grows the results themselves show us why.

No comments:

Post a Comment